Flora of Beijing: An Overview and Suggestions for Future Research

by Jinshuang Ma

Brooklyn Botanic Garden, 1000 Washington Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11225

by Quanru Liu

Department of Biology, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, 100875 China

Published online November 19, 2002

Abstract

This paper reviews Flora of Beijing (He, 1992), especially from the perspective of the standards of modern urban floras of western countries. The geography, land-use and population patterns, and vegetation of Beijing are discussed, as well as the history of Flora of Beijing. The vegetation of Beijing, which is situated in northern China, has been drastically altered by human activities; as a result, it is no longer characterized by the pine-oak mixed broad-leaved deciduous forests typical of the northern temperate region. Of the native species that remain, the following dominate: Pinus tabuliformis, Quercus spp., Acer spp., Koelreuteria paniculata, Vitex negundo var. heterophylla, Spiraea spp., Themeda japonica, and Lespedeza spp. Common cultivated species include Juglans regia, Castanea mollissima, Ziziphus jujuba, Corylus spp., Prunus armeniaca, Hydrangea bretschneideri, and Lonicera spp. Crop plants such as corn and wheat are also very common. Few species are endemic to Beijing, but some semiendemic species are shared with the neighboring province of Hebei. This paper includes lists of plants, including native, endemic, cultivated, nonnative, invasive, and weed species, as well as a list of relevant herbarium collections. We also make suggestions for future revisions of Flora of Beijing in the areas of description and taxonomy. We recommend more detailed categorization of species by origin (from native to cultivated, including plants introduced, escaped, and naturalized from gardens and parks); by scale and scope of distribution (detailing from worldwide to special or unique local distribution); by conservation ranking (using IUCN standards, for example); by habitat; and by utilization. Finally, regarding plant treatments, we suggest improvements in the stability of nomenclature, descriptions of taxa, and the quality and quantity of specimens used. We also recommend that information on and treatment of cultivated species, along with illustrations of species and maps, should be included in Flora of Beijing to promote a deeper understanding of the flora.

General Information

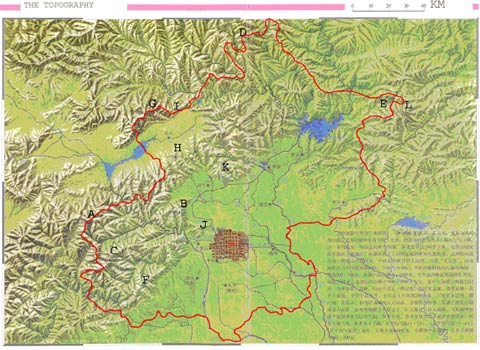

Beijing, the capital of the People's Republic of China, is one of the largest cities in the country; with more than 13 million people, it is also one of the largest cities in the world. More than 3,000 years old, Beijing has been China's capital since A.D. 1272 with only a few interruptions. Today, Beijing is an independently administered municipality, with an area of 16,808 square kilometers (6,490 square miles) stretching 160 kilometers from east to west and more than 180 kilometers from north to south. There are 18 districts and counties in the municipality: the districts of Xicheng, Dongcheng, Xuanwu, and Chongwen in the central city; Shijingshan, Haidian, Chaoyang, and Fengtai in the inner suburbs; and in the outer suburbs, Fangshan, Mentougou, Changping, Shunyi, Tongxian, and Daxing, as well as the counties of Yanqing, Huairou, Miyun, and Pinggu. The metropolitan area is composed of the first eight districts (see Map 1 and Table 1).

Geography

Beijing is located at latitude 39∫54'27" north and longitude 116∫23'17" east. It lies at the northwest end of the North China Plain, about 150 kilometers from the Gulf of Bohai in the southeast, at an elevation of 43.5 meters above sea level. About two thirds of the city is located on the plains, the rest on low mountains less than 1,000 meters high; the highest peak, at 2,303 meters, is in the northwest part of the city. The climate is a typical four-season continental climate of the Northern Hemisphere, with cold and dry winters and hot and wet summers. January is the coldest month (mean low -4∫C), and July is the warmest (mean high 26∫C). The frost period extends from October 14 to April 1. Beijing straddles Hardiness Zones 6 and 7, with mean annual minimum temperatures of -23.3∫C to -17.8∫C and -17.7∫C to -12.3∞C (for more on the Hardiness Zones of China, see http://www.plantapalm.com/vpe/hardiness/chinaHZ.gif). Annual precipitation is about 638.8 millimeters per year; most precipitation occurs in summer.

Land Use

During the past 50 years, the city's population has quadrupled (see Figure 1). However, it has grown little in area for the past several thousand years. Since the 1980s there has been a great deal of development, especially around the inner suburbs, but the mix of land uses in Beijing has not changed much.

Flora of Beijing

The inventory of the flora in and around Beijing began as early as the 1700s (Bretschneider, 1898); however, the modern Flora of Beijing was not completed until the middle of the last century. The first edition consisted of three volumes (He, 1962, 1964, 1975). The second, revised edition originally consisted of two volumes covering 169 families, 898 genera, and 2,088 species of vascular plants (He, 1984, 1987), including naturalized and escaped species cultivated in gardens and parks, and even some woody plants grown in greenhouses. It included nine families and 437 species more than the first edition. The second edition was expanded and reprinted in 1992, with an additional 118 species, bringing the total number of vascular plants in Beijing to 169 families, about 900 genera, and 2,206 species (He, 1992).

Vegetation

Geographically, the native vegetation of north China should be pine-oak mixed broad-leaved deciduous forest, especially in the lower mountains around the Beijing area. However, long-term large-scale human activities—deforestation, farmland clearing, and urbanization—have altered the original vegetation as well as its character. Within the city and in outlying suburban areas, farmland, orchards, and villages have long since replaced the native forest. In surrounding mountainous areas, most of the native vegetation is also gone, and oak (Quercus spp.), aspen (Populus davidiana), and birch (Betula spp.) have become dominant species, with lespedeza (Lespedeza spp.), early deutzia (Deutzia grandiflora), and spiraea (Spiraea spp.) in the shrub layer, and some grasses in the ground layer. See Table 2 for a list of representative trees and shrubs that can be found at various elevations.

Native Plants

The number of native vascular plants in Beijing, broken down by group (ferns, gymnosperms, and angiosperms) and location within the city (central city, inner suburbs, and outer suburbs) is shown in Table 3.

From these data, it is clear that most of the native plants are found in the suburbs, especially the outer suburbs. A significant number of vascular plants are found only in the remote mountainous areas of the outer suburbs. About one third of the total native flora (455 of 1,502 species) are found in these areas. In contrast, in the central city, as in most highly urbanized areas around the world, there are few native plants. See Map 2 for a breakdown of numbers of species and percentages of total native flora by district and county.

Endemic Plants

About 20 species in Flora of Beijing are endemic to Beijing or semiendemic (shared only with neighboring Hebei Province). The endemic and semiendemic species are listed in Table 4.

Cultivated Species

Of the 2,206 vascular plants found in Beijing, 704 (about one third) are nonnative species (i.e., introduced, escaped, naturalized, and/or cultivated). Of these, 257 species are widely cultivated, 152 species are occasionally cultivated, and 295 species are found only in gardens and parks, including in greenhouses (see Figure 2). Six hundred one species were introduced intentionally; 96 escaped or naturalized without cultivation; 7 are hybrids. Two hundred fifty species originated in other parts of China; 107 species are from Central and South America; 86 species are from North America; 72 species came from Europe; 65 species are from Africa; 63 species originated in other parts of Asia; 16 species are from the Mediterranean; and seven species came from Australia. The origin of the remaining species is unknown (see Figure 3).

See Table 5 for a list of cultivated species treated in Flora of Beijing, grouped by use.

See Table 6 for a list of the street trees of central Beijing.

Invasive Species

although invasion by nonnative species is accepted as a serious threat to natural environments as well as to human health and welfare worldwide (Boufford, 2001), there are little data on invasive species in Flora of Beijing. Research in this area is hampered by the lack of data and plant collections, and by the fact that no papers on this subject have yet been published. However, it is possible to extrapolate a few examples of invasive species from Flora of Beijing:

Common ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia): Widespread from the Yangtze River valley to northern China in the eastern part of the country, this species was very recently found in Beijing. Originally from North America, it has naturalized widely in China since 1970, although it was found as early as the 1930s (Zhu, Sha & Zhou, 1998) and was present in Europe and Russia well before that (Esipenko, 1991; Dimitriev, 1994; Nedoluzhko, 1984). This is a very harmful weed, both to crops and natural vegetation.

Cow soapwort (Vaccaria segetalis): Originally from Europe, the species naturalized in China around the 1950s, especially on farmland. It has been become an increasingly serious weed plant since the 1980s. It has also been cultivated and used as a medicinal plant in China.

Giant ragweed (Ambrosia trifida): Also from North America, this species was not found in Beijing before 1987, although it was present in the neighboring province of Hebei. However, when Flora of Beijing was reprinted in 1992, it was already found in more than five districts and counties in Beijing. This highly invasive weed has the potential to spread widely and quickly.

Johnsongrass (Sorghum halepense): This species was first found in Fengtai District in 1988. Now on the National Quarantine List of China, it is believed to have been introduced via seed-exchange stocks.

Spine cocklebur (Xanthium spinosum), smooth cocklebur (X. glabrum), and Italian cocklebur (X. italicum): All three of these species were found very recently (1988 and 1991). The first, from Europe and Asia, was introduced via seed-exchange stocks; the latter two came from North and South America and southern Europe. The fact that both these plants were found on farmland in Changping District at the same time suggests that they were introduced by chance with imported seed in seed-exchange stocks.

Toothed spurge (Euphorbia dentata): The first specimen of this North American native was collected in the Medical Plant Garden, Institute of Medical Plant Development, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences in the suburbs of Beijing around the 1960s. By the 1990s it had spread throughout the Botanic Garden, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences in Xiangshan, Haidian District. The status of the plant has not been updated since the first report in China (Ma & Wu, 1993). This species may have been introduced to China along with seed-exchange stocks.

The following species are the most commonly found weeds in Beijing: Chinese goosefoot (Chenopodium acuminatum); Japanese hop (Humulus scandens); common lagopsis (Lagopsis supine); barnyard grass (Echinochloa crusgallii); and crab grass/digitaria (Digitaria chrysoblephara).

Floristics

The flora of Beijing is a typical flora of the Northern Hemisphere with strong continental characteristics. Families with the highest number of species are listed in Table 7

Collections and Research

Several herbaria in Beijing include collections from the city as well as surrounding areas. Table 8 lists the major herbaria in Beijing, the years they were established, the number of specimens, and the focus of the collections.

As Table 8 indicates, herbarium collections of the flora around Beijing are quite extensive. This made it possible to revise Flora of Beijing in a short time (1975-1987); Beijing's was also the first revised edition among the local floras of China (Ma & Liu, 1998).

Most of the local flora research is done at the Herbarium of Beijing Normal University (BNU), led by Professor He Shi-Yuan with his students, as well as staff from other institutions who have joined the team. However, for various reasons, the floristic work has not been as extensive as urban floras in western countries. The BNU collections are still limited, and voucher specimens no longer exist for some taxa described in Flora of Beijing. Even in the revised edition (1987), there are still at least 24 species without voucher specimens; these have been described from previous records only. Nonnative species have not been emphasized—a subject of increasing importance now that China has opened its markets to the outside; more and more plants, introduced intentionally or unintentionally, will become invasive in coming years. Furthermore, the older generation of botanists is retiring, and there are few young scientists focused on local floristics. This is of particular concern in view of the work yet to be done in China to meet modern standards in western countries.

Though there are a number of herbarium collections in Beijing, as Table 8 shows, most of them were established fairly recently. The earliest herbaria in Beijing date to around the beginning of the last century. However, this does not mean that no research was done before that time: European botanists did a great deal of collecting in the area, and their research was published outside China. These works can be found in A Bibliography of Eastern Asiatic Botany (Merrill & Walker, 1938), in its supplement (Walker, 1960), and in History of European Botanical Discoveries in China (Bretschneider, 1898). In addition, important early collections from Beijing are deposited at major gardens and botanical institutions in Europe. These herbaria are crucial for tracking early records of the flora of Beijing.

Suggestions for Further Research

If Flora of Beijing is to meet the standards for modern urban floras, the following issues should be addressed in future revisions, especially if it is to serve as an example for future urban floras in China.

Description

Native and Nonnative Status

The origin of each species should be included in future editions of Flora of Beijing. "Native" indicates that the plant originates in the area where it was first encountered and described. "Nonnative" includes all plants other than native species, including those introduced, escaped, naturalized, and/or cultivated at parks and gardens, in greenhouses, and in yards. Special attention should be given to invasive species, a subject neglected in the past by both local and national floras.

Scale and Scope of Distribution

The distribution information by genus and species should be described in detail, from large to small scale: worldwide, Northern Hemisphere, Eurasia, East Asia, countrywide, region (northwest, north, northeast, etc.), province, county, district-town, etc., with as much local detail as possible. Latitude and longitude should also be recorded, and if feasible, Geographic Positioning Systems (GPS) data should be recorded and uploaded into Geographic Referencing Systems software; these technologies are among the fastest and best new tools for floristics fieldwork and collection management.

Conservation

The population abundance of the species—rated as widespread, common, occasional, rare, or only restricted in distribution (for example, found only on mountain summits)—should be recorded in as much detail as possible. In addition, every species should be classified by IUCN (World Conservation Union) global category: EX (extinct) EW (extinct in the wild), CR (critically endangered), VU (vulnerable), NT (near threatened), LC (least concern), DD (data deficient), and NE (not evaluated) (see http://www.redlist.org/). The China Plant Red Data Book (Fu, 1992), a reference for rare and endangered species in China, provides another option for classification. Such information is essential for surveying and protecting regional biodiversity.

Habitat

The habitat of each species should be described fully. Simply noting that it is found in the forest or on farmland is not sufficient. For example, the kind of forest should be described (i.e., whether it is native, secondary, or artificial). If a species is located on a mountain, the altitude, slope, and direction in which it is found should be noted. Similarly, the habitats of wetland plants should be specifically recorded (i.e., river, lake, reservoir, creek, mudflat, or bog). Other elements of description that should be incorporated include soils, surrounding human activities, and original vegetation.

Utilization

Human use of plants should also be noted in as much detail as possible. For example, it is not sufficient to say simply that a species has medical or horticultural uses in China; information on specific medicinal or horticultural uses should be supplied. This information plays a very important part in the Chinese history of botany.

Taxonomy

Name Stability—Nomenclature

Detailed information about the status of each species should be provided. If there is any disagreement about its nomenclature, this should be discussed at length. If there is any change in nomenclature, this should also be addressed. This kind of information has yet to be provided in detail. Taxonomic issues should be treated seriously, since in the long term, it is useful not only for current readers but also for future work.

Description

In classical floras like the current Flora of Beijing, description is complex—full descriptions are provided for both genera and species. Future revisions should treat the genera in detail; species and infraspecific taxa should be treated by their diagnostic characteristics only, combined with illustrations that can be easily understood and used by both professional botanists and amateurs. In cases of more than two species, there should be detailed keys, without ambiguous choices. Anything peculiar about a taxon, especially about its use, should also be highlighted.

Herbarium Specimens

Specimens provide the basic foundation for floras and are valuable vouchers for research. The current situation in Beijing is slightly better than most local areas in China. However, this does not mean the collections are adequate. Compared with western institutions, these collections are still of low quality, and there is much room for improvement. The quality of the collections needs to be improved, and the number of specimens needs to be increased to ensure that the collections represent an accurate sampling of the flora under investigation.

Information on Cultivated Plants

Cultivated plants should be treated like native species, and information on their origin and natural history should be included in their description. although the description should be simple, the information should be detailed and include, for example, whether the plants are widely cultivated like crops, occasionally cultivated in parks and gardens, or grown only in greenhouses or residential yards. Cultivated varieties should be listed and their distribution treated like that of other plants in the flora if possible. If a specimen is unavailable, its absence should be explained. The introduction and development of cultivated species should be discussed to better understand their potential effects on society and environment.

Illustrations

Illustrations are extremely useful in local floras, not only for professionals but also for the public. Each genus should be represented by at least one illustration. Also very helpful are illustrations of the diagnostic parts of each species. The simple black-and-white line drawings of the current Flora of China are insufficient, and in future revisions, color digital photos would be ideal, especially for online databases. Detailed maps may also be of great help to readers.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks are due to Dr. Steve Clemants, and Ms. Janet Marinelli at Brooklyn Botanic Garden, and to this paper's two anonymous reviewers for their comments, suggestions, and corrections.